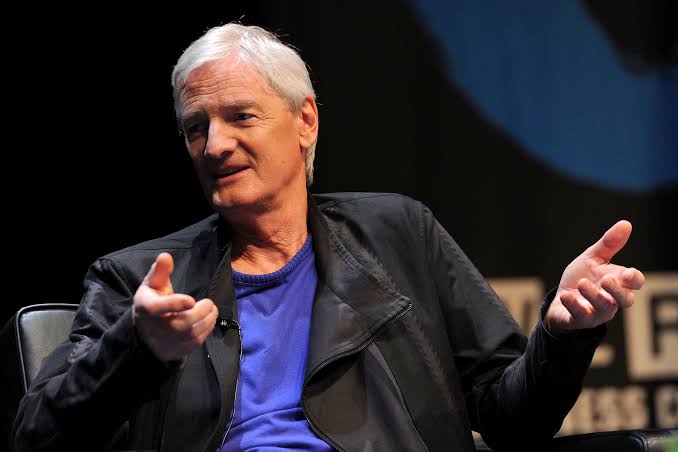

James Dyson didn’t just invent a better vacuum. He built a better way to think.

For mature professionals, founders, and creatives navigating rejection, stagnation, or the slow burn of long-term goals, Dyson’s journey offers more than inspiration. It offers a framework for building something that lasts—through grit, obsession, and a refusal to accept “good enough.”

The Problem No One Wanted to Solve

At 37, Dyson had already tasted success. His Ballbarrow—a wheelbarrow with a ball instead of a wheel—was selling well. He had revenue, recognition, and a growing business.

But one persistent frustration kept gnawing at him: his vacuum cleaner lost suction. The culprit? Dust-clogged bags.

Everyone else accepted it. Dyson didn’t.

He saw what others ignored: the problem wasn’t the vacuum. It was the bag. And that insight—simple, obvious, and dismissed by an entire industry—became the seed of a fifteen-year obsession.

Prototype 5,127

Dyson didn’t iterate casually. He built thousands of prototypes in his backyard workshop. Each failure wasn’t a setback—it was a data point. A refinement. A step closer.

His savings vanished. His business partner left. His board ousted him. His wife’s salary kept the family afloat. And still, he kept building.

This wasn’t blind persistence. It was strategic obsession. Dyson understood that the solution wasn’t incremental—it was foundational. He wasn’t improving the bag. He was eliminating it.

That kind of thinking doesn’t fit neatly into quarterly reports or investor decks. It requires solitude, conviction, and a willingness to be misunderstood.

Rejection as Market Research

When Dyson finally had a working prototype, he approached every major vacuum manufacturer—Hoover, Electrolux, and others.

All said no.

Why? Because his invention threatened their business model. They didn’t sell vacuums. They sold bags. A bagless vacuum wasn’t just disruptive—it was dangerous.

This is a crucial lesson for anyone pitching innovation: rejection isn’t always about the product. Sometimes, it’s about the system your product threatens.

Dyson didn’t pivot. He licensed his technology to Japan, where the G-Force cyclone vacuum became a luxury item. That revenue gave him the leverage to do what no one thought possible: build his own factory, launch his own brand, and sell directly to consumers.

The Long Game Pays Off

In 1993, Dyson launched the DC01 in the UK. Within 18 months, it was the best-selling vacuum in Britain. By 2005, Dyson vacuums outsold every competitor in the United States.

But Dyson didn’t stop.

At 60, he launched Dyson University to train engineers.

At 65, he invented the bladeless fan.

At 70, he was working on electric vehicles and air purification systems.

This wasn’t a career. It was a philosophy:

Solve the problem that others ignore. Build the thing that should exist. And never let rejection dictate your trajectory.

Lessons for Builders, Founders, and Creatives

Dyson’s story isn’t just about engineering. It’s about mindset. Here’s what mature professionals can take from his journey:

- Obsession is a strategy.

If you see a problem that no one else is solving and you can’t stop thinking about it—you’re not distracted. You’re onto something. - Rejection is intelligence.

Every “no” reveals who benefits from the status quo. Use that data to refine your strategy, not abandon it. - Build quietly, launch loudly.

Dyson spent years in solitude before going public. Protect your idea until it’s ready to withstand scrutiny. - Legacy is built in the workshop.

Not in pitch meetings, not in press releases. In the quiet, repetitive work of refining something that doesn’t yet exist. - Disruption is expensive.

It costs time, money, relationships, and reputation. But if the idea is sound, the payoff is exponential.

Final Thought: What Are You Refusing to Accept?

Dyson refused to accept that vacuums had to lose suction. That bags were necessary. That rejection meant failure.

What are you accepting today that might be the very thing holding your idea back?

What problem have you normalized because “that’s just how it works”?

If you’re on prototype 300, keep going.

If you’ve been rejected by every major player, good. That means you’re building something they didn’t see coming.

James Dyson didn’t just invent a better vacuum. He built a better way to think.

And for those willing to play the long game, that mindset might be the most valuable product of all.